4.1 FAA Awareness

At 8:00 on September 11, 2001, American Airlines Flight 11 began its takeoff roll at Logan Airport in Boston. A Boeing 767, American 11 was bound for Los Angeles with 81 passengers and 11 crewmembers.[i] By 8:09, American 11 had been passed from air traffic control at Logan Airport to Boston’s regional en route center in Nashua, NH, some fifty miles from Boston.[ii] The Boston controller at the Boston Sector Radar Position directed the flight to “climb and maintain level two eight zero.”[iii]

The controller followed this, at 8:10, with an instruction to “climb maintain flight level two niner zero,” which was affirmed by American 11.[iv] At 8:13, the controller instructed the flight to “turn twenty degrees right,” which the flight acknowledged: “twenty right American 11.”[v]

This was the last transmission to which the flight responded.

Sixteen seconds after receiving the acknowledgment from the pilot of the turn, the controller instructed the flight to “climb maintain level three five zero,” an ultimate cruising altitude of 35,000 feet.[vi] When there was no response, the controller repeated the command ten seconds later, and then tried repeatedly to raise the flight.

According to the controller, at that point, he thought “maybe the pilots weren’t paying attention, or there’s something wrong with the frequency.” He used the emergency frequency to try and [reach] the pilot. There was still no response.”[vii] Indeed, numerous controllers interviewed at various FAA facilities stated it was a common occurrence prior to 9/11 to lose radio contact with pilots of commercial aircraft for a brief period of time. Controllers attributed the frequent losses of radio contact to electrical problems, pilot inattentiveness, failure to change frequencies and other examples unrelated to hijackings.[viii]

At this point – from 8:15 until 8:24 on the transcript – the Boston sector controller attempted to contact American 11 nine times, all unsuccessfully.[ix] At 8:21, American 11 changed course, heading northwest, and someone turned off the transponder. With a turned off transponder the information available to the controller was severely compromised: controllers could receive data on the plane’s location, but could only loosely approximate its speed, had no way of knowing or even guessing its altitude, and could only identify it as a “primary radar target,” not as a specific squawking flight.[x] The controller “very quietly turned to the supervisor and said, `Would you please come over here? I think something is seriously wrong with this plane. I don’t know what. It’s either mechanical, electrical, I think, but I’m not sure.’” At this point, neither the controller nor his supervisor suspected hijacking.[xi] The supervisor instructed the controller to follow the standard operating procedures for the handling of a “no radio” (known as “NORDO”) aircraft.[xii] Accordingly, the controller checked the working condition of his own equipment, then attempted to raise the flight on the 121.5 guard frequency. Boston Center controllers then tried to contact the airline to establish communication with the flight, and became more concerned when the flight began to move through the arrival route for Logan Airport, and then toward another sector’s airspace.[xiii]

082350 AA11 check everything company.mp3

About five minutes after the hijacking began, Flight Attendant Betty Ong contacted the American Airlines Southeastern Reservation Office in North Carolina to report an emergency aboard the flight. Following is a portion of the tape of that call.

The controllers moved “all the airplanes … from Albany to New York to Syracuse, NY out of the way because that’s the track he was going on,” and searched from aircraft to aircraft on the company frequency in an effort to have another pilot contact American 11.

At 8:24:38, American 11 began a turn to the south and the following transmission came from American 11:

082444 AA11 keying 2 transmissions.mp3

This Boston Sector controller heard something unintelligible over the radio, and did not hear the specific words “[w]e have some planes” at the time. The next transmission came seconds later:

The controller has told the media and Commission staff during interviews, when he heard this second transmission, he “felt from those voices the terror” and immediately knew something was very wrong. He knew it was a hijack.”[xiv]

Controllers at Boston Center discussed attempts to contact American 11, the aircraft’s altitude and whether someone had taken over the cockpit of the aircraft:

082453 AA11 check sup already Did.mp3

082542 AA11 point out enter new route.mp3

082655 AA11 take back look west albany.mp3

The controller alerted his supervisor to the threatening communication. The supervisor assigned a senior controller to assist the American 11 controller, and redoubled efforts to ascertain the flight’s altitude.[xv] Because the initial transmission was not heard clearly, the Manager of Boston Center instructed the Center’s Quality Assurance Specialist to “pull the tape” of the radio transmission, listen to it closely, and report on what he heard.[xvi] Between 8:25 and 8:32, in accordance with the FAA protocol, Boston Center managers started notifying their chain of command that American 11 had been hijacked. At 8:28, Boston Center called the Command Center in Herndon, Virginia to advise management that it believed American 11 had been hijacked and was heading toward New York Center’s airspace. By this point in time, American 11 had taken a dramatic turn to the south. Command Center immediately established a teleconference between Boston, New York and Cleveland Centers to allow Boston Center to provide situational awareness to the centers that adjoined Boston in the event the rogue aircraft entered their airspace.[xvii]

082924 AA11 ZBW notification ZOB ZNY 5115 line.mp3

The Command Center subsequently provided the following update on the situation to an unknown air traffic control facility:

083053 AA11 pascione summation to unknown 5115 Line .mp3

At 8:32, the Command Center passed word of a possible hijacking to the Operations Center at FAA headquarters. The duty officer replied that security personnel at headquarters had just begun discussing the hijack situation on a conference call with the New England Regional office.

Also at 8:32, Michael Woodward of American Airlines took a call from Flight Attendant Madeline “Amy” Sweeney that lasted approximately twelve minutes. Although the call was not taped, Woodward’s colleague, Nancy Wyatt, standing at his side, contacted Ray Howland in the American Airlines System Operations Center (SOC) to report the content of the ongoing call between Woodward and Amy Sweeney. Wyatt was able to relay information to the SOC as she heard Woodward’s side of the conversation and read the notes he was taking. Following are two excerpts, which span several minutes, from the call to Howland.

Boston flight service segment one.mp3

Boston flight service segment two.mp3

At 8:34, as FAA headquarters received its initial notification that American 11 had been hijacked, the Boston sector controller received a third transmission from American 11.

083359 Nobody move please going back to airport.mp3

In succeeding minutes, controllers in both Boston Center and New York Center attempted to ascertain the altitude of the southbound American 11.[xviii]

083556 AA11 ZNY Kingston point out to Kennedy.mp3

Information about what was going on within American 11 started to get conveyed within the ATC system. At 8:40, Boston Center, through the Command Center, provided a report to New York TRACON on American 11. And at 8:43, a Command Center air traffic specialist warned Washington en route center that American 11 was a “possible hijack” and would be headed towards Washington Center’s airspace if it continued on a southbound track.

083940 ZBW TRACON by Sparta.mp3

American 11 crashed into the North Tower of the World Trade Center at 8:46:40. [Word of the crash of an airplane began to work its way quickly through the FAA’s New York Center.]

084739 AA11 Discussion To First Impact Line 5114.mp3

085017 AA11 ZNY Major Fire WTC.mp3

4.2 Military Notification and Response

After Boston Center’s managers notified the New England Region of the events concerning American 11, they did not wait for military assistance as notification was passed up the chain of command to FAA headquarters. In an attempt to get fighter aircraft airborne to track American 11, Boston Center’s managers took the initiative and called a manager at the FAA Cape Cod facility at 8:34. They asked the Cape Cod manager to contact Otis Air Force Base in Cape Cod, Massachusetts to get fighters airborne to “tail” the hijacked aircraft.[xix]

083355 Bueno call to Cape Tracon.mp3

Boston Center managers also tried to obtain assistance from a former alert site in Atlantic City, unaware that it had been phased out.

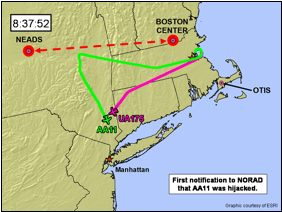

At 8:37:52, Boston Center’s persistence finally paid dividends. They called the North American Aerospace Defense Command’s (NORAD) Northeast Air Defense Sector (NEADS) and notified NEADS about the suspected hijacking of American 11.[xx]

083724 AA11 ZBW call to Powell and reaction.mp3

083815 AA11 Powell Cooper Deskins.mp3

The United States’ military defense of its homeland on 9/11 began with this call. Indeed, this was the first notification received by the military – at any level – that American [11] had been hijacked. NEADS promptly ordered to battle stations the two F-15 alert aircraft at Otis Air Force Base, Massachusetts, about 153 miles away from New York City.[xxi]

083922 NEADS weapons and MCC battle stations.mp3

084000 AA11 Panta 45 battle stations cape tape.mp3

At NEADS, the reported hijack was relayed immediately to Battle Commander Colonel Robert Marr, who was stationed in the Battle Cab in preparation for a scheduled NORAD exercise. Col. Marr asked the same question – confirming that the hijacking was “real-world” – then ordered fighter pilots at Otis Air Force Base in Massachusetts to battle-stations.[xxii]

He then phoned Maj. General Larry Arnold, commanding General of the First Air Force and CONR. Col. Marr advised him of the situation, and sought authorization to scramble the Otis fighters in response to the reported hijacking. General Arnold instructed Col. Marr “to go ahead and scramble the airplanes and we’d get permission later. And the reason for that is that the procedure … if you follow the book, is they [law enforcement officials] go to the duty officer of the national military center, who in turn makes an inquiry to NORAD for the availability of fighters, who then gets permission from someone representing the Secretary of Defense. Once that is approved then we scramble an aircraft. We didn’t wait for that.”[xxiii] General Arnold then picked up the phone and talked to the operations deputy up at NORAD and said, “Yeah, we’ll work with the National Military Command Center (NMCC). Go ahead and scramble the aircraft.”[xxiv]

He then phoned Maj. General Larry Arnold, commanding General of the First Air Force and CONR. Col. Marr advised him of the situation, and sought authorization to scramble the Otis fighters in response to the reported hijacking. General Arnold instructed Col. Marr “to go ahead and scramble the airplanes and we’d get permission later. And the reason for that is that the procedure … if you follow the book, is they [law enforcement officials] go to the duty officer of the national military center, who in turn makes an inquiry to NORAD for the availability of fighters, who then gets permission from someone representing the Secretary of Defense. Once that is approved then we scramble an aircraft. We didn’t wait for that.”[xxiii] General Arnold then picked up the phone and talked to the operations deputy up at NORAD and said, “Yeah, we’ll work with the National Military Command Center (NMCC). Go ahead and scramble the aircraft.”[xxiv]

The scramble order was passed from the Battle Commander (BC) to the Mission Crew Commander (MCC), who passed the order to the Weapons Director (WD).[xxv] Almost immediately, however, a problem arose. The Weapons Director asked: “MCC. I don’t know where I’m scrambling these guys to. I need a direction, a destination.”[xxvi] Because the hijackers had turned off the plane’s transponder, the plane appeared only as a primary track on radar.

084259 NEADS SOCC work to scramble.mp3

NEADS personnel spent the next minutes searching their radar scopes for the elusive primary radar track, as NEADS’ Identification (ID) Technicians contacted the Military Operations Specialist (MOS) Desk (a civilian employee position at FAA Centers) at Boston Center in an effort to locate the aircraft:

083800 AA11 NEADS ID techs react to Powell.mp3

F-15 fighters were ordered scrambled at 8:46 from Otis Air Force Base and vectored toward military airspace off the coast of Long Island.[xxvii]

084555 NEADS Powell Otis scramble.mp3

As the order to scramble Otis fighters came at 8:46, American 11 was hitting the World Trade Center and United 175 was being hijacked in New York Center’s airspace. The military did not hear anything about United 175 until it crashed into the South Tower of the World Trade Center.

As the order to scramble Otis fighters came at 8:46, American 11 was hitting the World Trade Center and United 175 was being hijacked in New York Center’s airspace. The military did not hear anything about United 175 until it crashed into the South Tower of the World Trade Center.

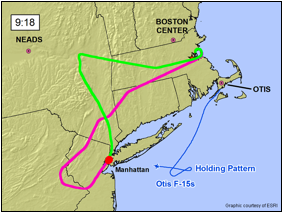

Working over the phone with the FAA Center in Boston, at least one NEADS tracker found a primary track roughly eight miles east-northeast of Manhattan, but the track faded before he could confirm it with Boston Center.[xxviii] Unbeknownst to the military, the Otis fighters were scrambled [at] nearly the exact time that American 11 crashed into the North Tower. Radar data show the Otis fighters were airborne at 8:53. [xxix]

The Mission Crew Commander explained to the Battle Cab the plan:

084629 NEADS MCC summary for BC 25 miles Z point.mp3

Shortly after 8:50, while NEADS personnel struggled to locate American 11, word reached the floor that a plane had hit the World Trade Center.[xxx]

085207 NEADS learns of WTC continues scramble.mp3

The initial reaction of the Mission Crew Commander was to send the fighters directly to New York in response to the news of the crash. Upon being advised, however, that the quickest route would be to bring the fighters out away from the New York area traffic, the decision was made to bring the fighters down to military air space and to “hold as needed.”[xxxi]

085340 Panta hold and work with FAA DRM 1 CH 2.mp3

4.3 Commission Findings and Assessment

The interplay at the operational levels of the FAA and NORAD regarding American 11 is notable in several respects. First, and most important, Boston Center and NEADS took immediate actions to facilitate a quicker response than a strict following of the official protocols would have allowed for. Boston Center elected to request assistance directly from the Northeast Air Defense Sector. When the request reached NEADS, the Battle Commander and the CONR Commander, rather than seeking authorization to scramble aircraft through the chain of command and, ultimately, the Secretary of Defense, chose to authorize the action on their own and, as General Arnold (CONR Commander) put it, “seek the authorities later.” It is difficult to fault either decision. Given the emergent nature of the situation, the reports of “trouble in the cockpit,” and the fact that there was no easily identified transponder signal emitted from the aircraft, the necessity to shortcut the hijack protocols seems apparent. It is clear, moreover, that the protocols themselves were ill-suited to the American 11 event; the multi-layered notification and approval process assumed a “classic” hijack scenario in which there is ample time for notice to occur, there is no difficulty in locating the aircraft, the hijackers intend to land the aircraft somewhere, and the military’s role is limited to identification and escort of the aircraft. Indeed, the hijack protocols were not reasserted on 9/11 until the attacks were completed.

However, bypassing the established protocols for air emergencies, though justified in the case of American 11, may have had an unintended ill effect as the day wore on; leadership at the national levels at the FAA and DoD [was] not involved – or [was] involved only after the fact – in the critical decision making and the evolving situational awareness regarding American 11. As the Commission has presented in its June 2004 public hearing and in the official “9/11 Commission Report,” they [national leaders] would remain largely irrelevant to the critical decision making and unaware of the evolving situation “on the ground” until the attacks were completed.

The critical information NEADS received would continue to come from Boston Center, which relayed information as it was overheard on FAA teleconferences. Indeed, at one point that morning the Mission Crew Commander, in the absence of regular communication from anyone else at FAA, encouraged the Military position at Boston Center to continue to provide information: “if you get anything, if you – any of your controllers see anything that looks kind of squirrelly, just give us a yell. We’ll get those fighters in that location.”[xxxii] The NEADS ID Technicians would complain repeatedly that morning: “Washington has no clue what the hell is going on… Washington has no clue.”[xxxiii]

0944 Washington has no clue.mp3

The Boston Military FAA representative, when interviewed, expressed astonishment that he had been the principal source of information for the NEADS personnel on the morning of 9/11; he stated his belief that he must have been one of several FAA sources constantly updating NEADS that morning.[xxxiv] No open line was established between NEADS and CONR and either FAA headquarters or the Command Center at Herndon until the attacks were virtually over.

It is clear that, as the order to scramble came at 8:46, just as American 11 was hitting the World Trade Center, the military had insufficient notice of the hijacking to position its assets to respond. This reality would also be repeated throughout the morning. Indeed, the eight minutes’ notice that NEADS had of American 11 would prove to be the most notice the sector would receive that morning of any of the hijackings, and the sector’s inability to locate the primary radar track until the last few readings would also recur.

« Previous Section | Table of Contents | Next Section »

[i] William A. Scott interview (May 23, 2003); FAA Summary of Air Traffic Hijack Events, 9/11/01.

[ii] “Full Transcript; Aircraft Accident; AAL11; New York, NY; September 11, 2001,” 46R, at 8:09:17.

[iii] “Full Transcript; Aircraft Accident; AAL11; New York, NY; September 11, 2001,” 46R, at 8:09:22.

[iv]“Full Transcript; Aircraft Accident; AAL11; New York, NY; September 11, 2001,” 46R, at 8:10:13.

[v] “Full Transcript; Aircraft Accident; AAL11; New York, NY; September 11, 2001,” 46R, at 8:13:29.

[vi] “Full Transcript; Aircraft Accident; AAL11; New York, NY; September 11, 2001,” 46R, at 8:13:47.

[vii] Peter Zalewski interview (Sept. 22, 2003).

[viii] Peter Zalewski interview (Sept. 22, 2003); John Schippani interview (Sept. 22, 2004).

[ix] “Full Transcript; Aircraft Accident; AAL11; New York, NY; September 11, 2001,” 46R, at 8:15:15, 8:15:22, 8:15:49, 8:16:32, 8:17:05, 8:17:56, 8:18:56, 8:20:08, and 8:22:27.

[x] William A. Scott testimony (May 23, 2003).

[xi] Peter Zalewski interview (Sept. 22, 2003); John Schippani interview (Sept, 22, 2003).

[xii] John Schippani interview (Sept. 22, 2003).

[xiii] Peter Zalewski interview (Sept. 22, 2003).

[xiv] Peter Zalewski interview (Sept. 22, 2003).

[xv] John Schippani interview (Sept. 22, 2003).

[xvi] Terry Biggio interviews (Sept. 22, 2003 and Jan. 8, 2004); Robert Jones interview (Sept. 22, 2003).

[xvii] FAA audio file, Herndon Command Center, position # 15, at 8:28; Daniel Bueno interview (Sept. 22, 2003).

[xviii] FAA audio file, Herndon Command Center, position 14, at 8:48.

[xix] Terry Biggio interviews (Sept. 22, 2003 and Jan. 8, 2004); Daniel Bueno interview (Sept. 22, 2003); FAA audio file, Herndon Command Center New York Center position, line 5114, September 11, 2001, from 8:30 to 8:46.

[xx] Published timelines from the FAA and NORAD place the notification time at 8:40. NEADS recordings indicate, however, that the actual call came in at 8:37:15 to the Weapons Director Technician position, Channel 14.

[xxi] William A. Scott testimony (May 23, 2003).

[xxii] Published timelines from the FAA and NORAD place the notification time at 8:40. NEADS recordings indicate, however, that the actual call came in at 8:37:15 to the Weapons Director Technician position, Channel 14. Robert Marr interview (Jan. 23, 2004).

[xxiii] Larry Arnold testimony (May 23, 2003).

[xxiv] Larry Arnold, quoted in Air War Over America, by Leslie Filson, p. 56.

[xxv] NEADS audio file, Mission Crew Commander position, Channel 2, at 8:44:48.

[xxvi] NEADS audio file, Mission Crew Commander position, Channel 2, at 8:44:58.

[xxvii] NEADS audio file, Mission Crew Commander position, Channel 2, at 8:58:00.

[xxviii] Joseph McCain interview (Oct. 28, 2003).

[xxix] Reported initially on NEADS audio file, Mission Crew Commander position, Channel 2, at 8:54.07. Actual airborne time: 8:53:00, as confirmed by Commission staff analysis of DOD radar files, 84th Radar Evaluation Squadron, “9/11 Autoplay,” undated.

[xxx] NEADS audio file, Identification Technician position, channel 5, at 8:51:13; NEADS audio file, Identification Technician position, channel 7, at 8:51:20; NEADS audio file, Mission Crew Commander position, Channel 2, at 8:52:00.

[xxxi] NEADS audio file, Mission Crew Commander position, Channel 2,, at 8:54:55.

[xxxii] NEADS audio file, Identification Technician position, channel 5, at 9:18:11.

[xxxiii] ID Tech, Ch. 5, at 13:44:15.

[xxxiv] Collin Scoggins interview (Sept. 22, 2003).

No responses yet